Beyond WSET: Rediscovering the Red Wines of Rías Baixas

We take a nostalgic journey to rediscover the winemaking traditions that Albariño gradually pushed aside

I was having a little look, just out of curiosity, at the book a colleague lent me who’s been preparing this year for the WSET Level 4 — the Diploma — to see what they have to say about Galicia. Not much. Rías Baixas and Albariño get in-depth coverage, and the rest of the regions, varieties, and wine styles are mentioned like tiny satellites orbiting that giant monster, almost as an afterthought.

That’s why I wanted to write this post — not as a critique, but as an educational complement for anyone who might find it useful or be interested. I say it’s not a critique because, more than at WSET as an educational institution, the ones who really need a nudge are the D.O.s, so they get moving and build relationships with teaching institutions that go deeper into our wine regions — although I know that Valdeorras, for example, has made some initiatives this year.

Then we — Galicians — complain about how hard it is to sell our wines abroad. Well, here’s an opportunity. But it has to be seized, eh? You can’t just sit on your hands; sometimes you’ve got to roll up your sleeves. Let’s not forget that teaching institutions like WSET are the gateway for the education of countless sommeliers — including yours truly — and if they connect with our wines, guess who’s going to list them on wine lists and shelves all over the world? Strategic vision is missing.

As always, I wander off on my own tangents — sorry about that.

Many of you may not know, but before the 1980s, the wine produced along the Galician coast had a different predominant color than what we imagine today. Before Albariño took over Salnés and redefined the current Rías Baixas map, red varieties were a common presence, forming the heart of Galician viticulture.

In O Salnés, O Rosal, Soutomaior, and especially O Condado, reds were the everyday wine — the one that fed families and accompanied daily life. Varieties like Espadeiro, Caíño, Brancellao, Pedral, Castañal, and Sousón formed the backbone of local viticulture, while Albariño was considered a prestigious wine. This wasn’t just about agriculture; it shaped the culture and identity of the region: reds were essential both on the table and in local trade.

The Albariño boom in the 20th century radically changed the landscape. Red varieties were gradually pushed aside; many vineyards were uprooted or converted to Albariño, because that variety made money. As a result, part of this historical varietal heritage was lost or reduced to isolated plots, many outside the official D.O. registers. Yet, the memory of these vines and their cultivation remains documented in literature, historical records, and testimonies, recalling a past in which reds were the everyday wine of the Atlantic coast — drunk at the table, in taverns, or at village festivals. Whites like Albariño were reserved for special occasions, to impress, or even to settle a favor.

Albariño was always there, but suddenly it became Galicia’s big economic promise. Its success brought prosperity but also homogeneity to an industry built more on money than on respecting a viticultural tradition. Today, fortunately, more and more coastal wineries are giving those wines back their voice and reason to exist.

Viticulture was peasant, mixed, deeply domestic. Each smallholding plot combined other crops like corn or vegetables with a few rows of vines. Beneath the vines, greens or legumes were planted, and wine was made without any commercial pretension. And those tall trellises not only protected the grapes from moisture but also shaded the vegetable plots. It was balanced agriculture, not monoculture.

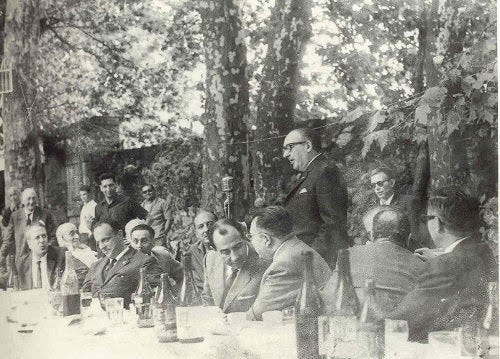

Winemaking practices were simple but consistent. I found curious details showing that in villages like Fefiñáns, it was common to transfer the new wine into barrels that still held some of the previous year’s wine, creating a kind of improvised ‘solera’ that maintained continuity of flavor. Many growers lacked presses and trod the grapes by foot, producing red wines that were dense, tannic, slightly rough, but pleasantly rustic. These were wines to accompany daily work rather than for commercial sale.

At the end of the 19th century, phylloxera profoundly disrupted this balance. The coast was replanted on American rootstocks — Riparia, Rupestris, or Aramón hybrids — and much of the varietal heritage was lost. Old red vines, as I mentioned before, disappeared or were confined to family plots. From the 1950s, vineyards began to be replanted with a single variety, encouraged by promises of prosperity and recognition. In 1953, the Festa do Albariño in Cambados marked the start of a new narrative.

The success was undeniable but also homogeneous. What had been a diverse, mixed viticulture, with reds and whites sharing the soil, was reduced to a single voice. Red grapes were relegated to memory or neglect. In many villages, the elders would say that ‘real wine had lost its color’.

It’s interesting to highlight, because it’s part of our idiosyncrasy, that when vineyards were being replanted after phylloxera, the people of Salnés sought ways to produce wine without waiting decades for the traditional varieties to recover. That’s when they began using resistant hybrids — crosses between American and European grapes — to make the red wine we now know as Barrantes. But beware: we mustn’t confuse this Tinto Barrantes, deeply rooted in popular culture, with the wines made from local grapes in the past, nor with those being revived and valued today. The grape used, Folla Redonda, is a variety designed to resist the plague, and its commercialization is prohibited because hybrids are not officially recognized for D.O. wine production. The most optimistic horizon, according to technicians and local authorities, points to 2027 as the year Folla Redonda could be officially registered, potentially opening the door to legal commercialization of Tinto Barrantes. Meanwhile, its consumption remains local, and every May the Festa do Viño de Barrantes celebrates it.

However, not all Vitis Vinifera red vines were eradicated. On the edges of Salnés, in Rubiós or the slopes of O Rosal, small local vineyards survived, twisted and silent, waiting for another chance. In recent years, a handful of growers have turned their eyes back to them. Not out of romanticism, but because they understand that the true coastal heritage also lies in that memory, rooted deeply in local history.

The varieties

According to local references, here’s a glimpse of how the wines were:

Espadeiro was the dominant grape in Salnés. Small clusters, thin skins, producing light reds with lively acidity and translucent color. The backbone of the wines our grandparents filled in their barrels, drunk with bread and conversation under the trellises.

Caíño, or Tinta Femia, stands out for its tense acidity and vegetal nuances. In the 19th century, it was considered ‘the queen of Galician reds’, noted for producing wines of high quality and aging potential.

Loureiro Tinta, almost forgotten, has a rustic delicacy with lively, saline acidity giving it a unique personality. Rarely used as a varietal, it usually complements other grapes in regional wines.

Castañal was grown mainly in southern Pontevedra (O Rosal), mentioned in the early 20th century as a characteristic variety. It offers a rustic, almost mushroom-like nose but grows expressive and saline on the palate.

Pedral, humble in Condado, low-yielding but authentic. Appreciated for producing wines with good structure and aging potential. Nowadays, some growers work it in a more ethereal way, to make it accessible sooner rather than waiting years.

Regarding Sousón, were it not for its color (it taints quite a lot), this variety could be to Galicia what Nebbiolo is to Piemonte. I mean, they don’t share the same varietal identity, but it’s true that Sousón is stubborn: high in acidity, tannins, and structure, requiring years of patience to deliver wines of extraordinary elegance. In my view, the red grape of Galicia’s future.

Brancellao, aromatic and spicy, is another great Galician red with the potential to produce wines of remarkable elegance and complexity.

After this brief tour — just scratching the surface — of the red varietal universe of the region, I’ll return in the next post to talk about nine coastal reds you absolutely have to try. So if you haven’t subscribed to the blog yet, now’s a good time, so you don’t miss the content I’m working on.

🍷

#7 Top 50 Sommeliers in the UK 2025

Thank you for all of this fantastic information about one of my favorite wine regions!